A report published by the Surveillance Resistance Lab (formerly the Surveillance, Tech and Immigration Policing Project) and the Transnational Institute

by Mizue Aizeki, Geoffrey Boyce, Todd Miller, Joseph Nevins and Miriam Ticktin

The report, “Smart Borders or a Humane World?” delves into the rhetoric of “smart borders” to explore their ties to a broad regime of border policing and exclusion that greatly harms migrants and refugees who either seek or already make their home in the United States. Investment in an approach centered on border and immigrant policing, it argues, is incompatible with the realization of a just and humane world.

A report published by the Surveillance Resistance Lab (formerly Immigrant Defense Project’s Surveillance, Tech & Immigration Policing Project), and the Transnational Institute. Endorsed by: ACLU of Vermont, American Friends Service Committee (US-Mexico Border Program), Black Alliance for Just Immigration, Detention Watch Network, Just Futures Law, Grassroots Global Justice, Grassroots International, Migrant Justice, Mijente, Migration Technology Monitor, No More Deaths, RGV No Border Wall Coalition, and the Southern Border Communities Coalition.

Five Core Harms of Border Policing

The report highlights five core harms of border policing.

A boom in the border and surveillance industrial complex.

The growing policing of immigrants and their communities, the borderlands, & society as a whole.

The separation and undermining of families and their communities.

The maiming and killing of large numbers of border crossers.

The exacerbation of socioeconomic inequality.

Report Graphics

Executive Summary

On January 20, 2021, his first day in office, President Biden issued an executive order pausing the remaining construction of the southern border wall initiated during the Trump administration. Soon after, the White House sent a bill to Congress, the US Citizenship Act of 2021, calling for the deployment of “smart technology” to “manage and secure the southern border.”

This report delves into the rhetoric of “smart borders” to explore their ties to a broad regime of border policing and exclusion that greatly harms migrants and refugees who either seek or already make their home in the United States. Investment in an approach centered on border and immigrant policing, it argues, is incompatible with the realization of a just and humane world.

Case studies from Chula Vista, California, the European Union, Honduras, Mississippi, and the Tohono O’odham Nation provide substance to this analysis. So, too, do graphics that illustrate the militarized US border strategy and the associated expansion of borders; the growing border industrial complex; the spreading web of surveillance; and the relationship between wall-building, global inequality, and climate change-related displacement.

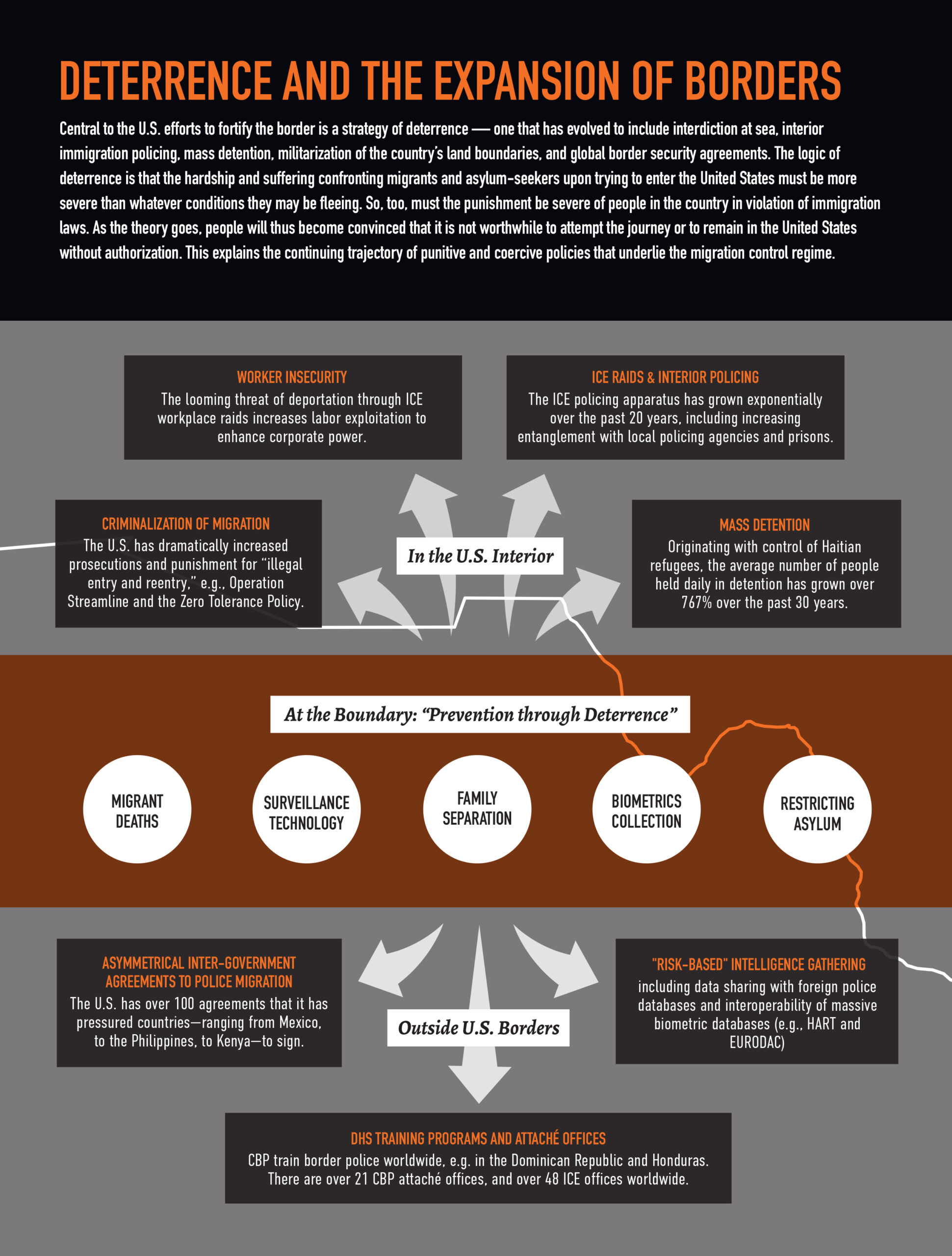

As the report traces, the embrace of “smart borders” emerged in the aftermath of 9/11. Smart borders involve the expanded use of surveillance and monitoring technologies including cameras, drones, biometrics, and motion sensors to make a border more effective in stopping unwanted migration and keeping track of migrants. Championing smart borders was—and remains—one of three key pillars of US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) strategy, along with physical barriers and personnel. Smart borders are also embedded in a logic of deterrence, which seeks, by way of militarized border infrastructure, detention, and deportation, to make unwanted migration so brutal and painful that it will dissuade people from even trying to enter the United States without authorization.

The use of technology by US border agencies is not new. As early as 1919, the US government deployed armed aerial surveillance and reconnaissance of the border region. However, contemporary smart borders are unique in the sophistication of the technologies they embody, the scope of the personal data they are able to collect, and the integration of these systems with one another. They are also more extensively used within and beyond the United States than ever. This is reflected in the increasingly global presence of CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE): the former has 23 offices and the latter 48 offices outside the United States.

The report details some of the more prominent deployments of smart-border technologies. In addition to drones and automatic license plate readers, such technologies include:

Integrated Fixed Towers (IFTs), built by Elbit Systems of America, a subsidiary of the Israeli arms company. Elbit has built fifty IFTs throughout southern Arizona, each of which has daytime, night-vision, and thermal-energy cameras that can see at a distance of up to seven and a half miles, as well as a ground-sweeping radar with a radius of nearly thirteen miles.

Ankle monitors, enable ICE to track those with pending asylum applications and others under ICE supervision. Ankle shackles subject people to electronic incarceration with economic, social, psychological, and legal consequences. As of August 2019, there were over 43,000 individuals subject to this technology.

Migrant data analysis and tracking. ICE has worked closely with Palantir to develop two key tools. The first is the Investigative Case Management (ICM) platform that links records to multiple investigations. The second is FALCON Search and Analysis (FALCON-SA), which analyzes data from multiple databases run by DHS and law agencies, as well as from data streams linked to people’s internet and social media activity. These platforms enable ICE to apply artificial intelligence to vastly speed up the agency’s capacity and efficiency to detain and deport.

Embracing such technologies, many leading Democratic and some Republican politicians argue that a “smart” border offers a humane alternative to Trump-era immigration policy. Yet as this report shows, “smart” or not, all border policing shares a common goal: to control human beings and to deny entry to those deemed undesirable or undeserving. In other words, the goal of a “smart” border is not increased humaneness, but greater effectiveness in advancing this violent enterprise.

In substantiating this position, the report highlights and explores five core harms of US border policing:

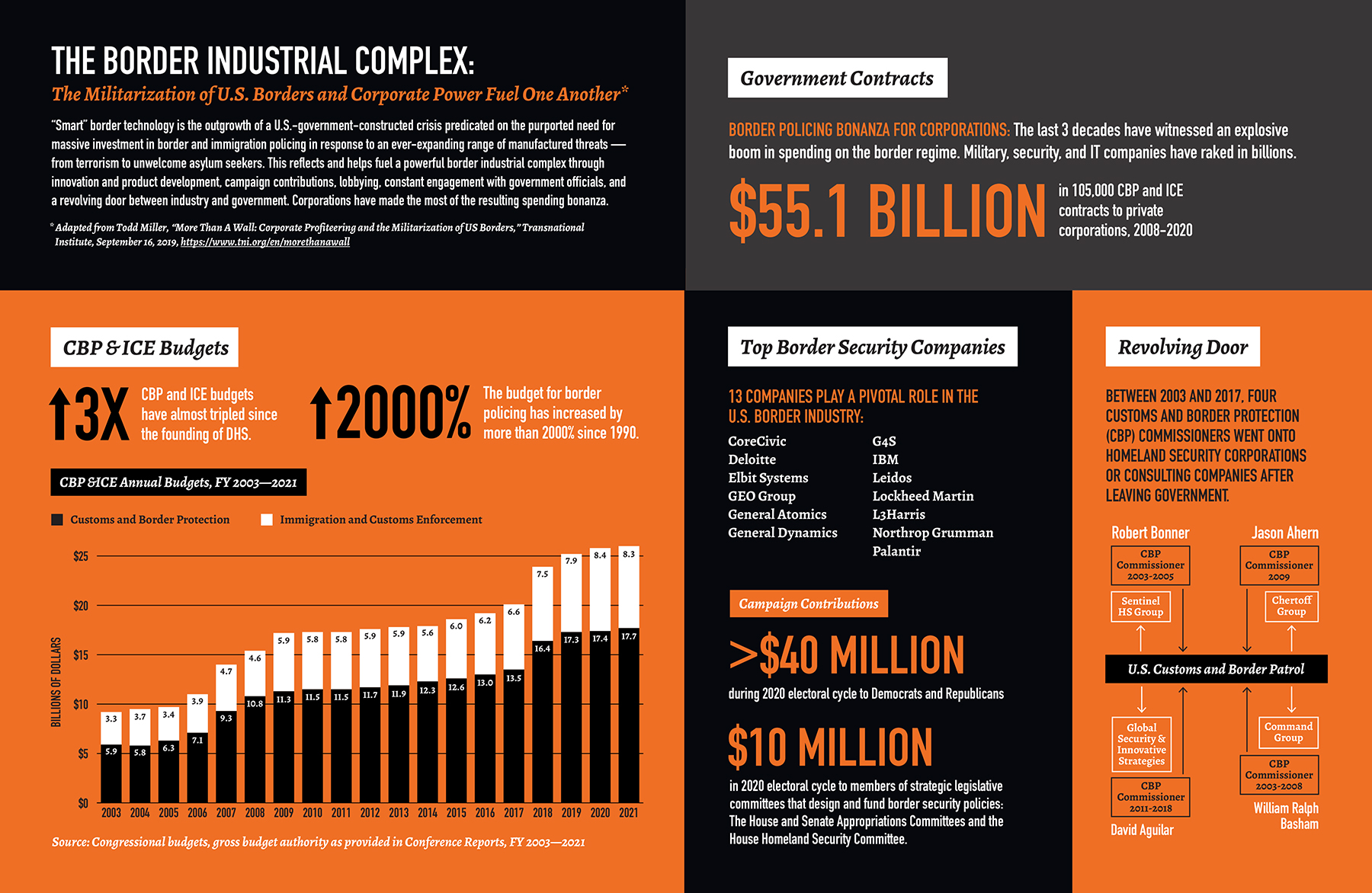

1) A boom in the border and surveillance industrial complex. Between 2008 and 2020, CBP and ICE issued 105,997 contracts worth $55.1 billion to private corporations—such as CoreCivic, Deloitte, Elbit Systems, GEO Group, General Atomics, G4S, IBM, Leidos, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Palantir—with ever more contracts for “smart border” technologies. The spending bonanza has provided a bottomless market for growth. There can never be “total” security and, thus, there will always be an alleged need for new technology to fill perceived gaps. Failure of any kind helps create a market for the next even more expensive product or service.

2) The growing policing of immigrants and their communities, the borderlands, and society as a whole. Via surveillance technologies, the capacity of the Department of Homeland Security to police and monitor individuals has grown tremendously. On any given day, for example GPS enabled ankle monitors are attached to the bodies of tens of thousands of noncitizens. Such targeted forms of surveillance are complemented by passive ones that monitor a growing swath of the US population. This is especially the case with the US borderlands with Mexico and Canada where CBP provides funding and equipment to local police to incentivize cooperation. CBP also uses such technologies to monitor social movements and political speech. In 2020, for example, CBP aerially surveilled Black Lives Matters protests in at least 15 cities. In addition, the capacity to arrest and detain noncitizens has grown dramatically, as ICE has vastly expanded its surveillance arsenal via, among other technologies, mobile fingerprinting devices and data analytics developed by Palantir to facilitate tracking and targeting of individuals.

3) Separation and undermining of families and communities. Trump’s zero-tolerance program made family separation a hot political issue. However, the dividing and harming of families have long been, and continue to be, outcomes of US border and immigration policy. For example, studies show that the arrest, detention, and/or deportation of family members cause symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Such symptoms can lead to decline in school performance, negative impacts on health and nutrition, poverty, and economic insecurity—not only for those who have been forcibly deported, but also for those who remain in the United States.

4) The maiming and killing of large numbers of border crossers. The US Border Patrol reports an annual average of 355 deaths between 1998 and 2019, or about one death per day over a twenty-two-year period. Because many bodies are not recovered, however, the true figure is far higher. A strengthened border-policing apparatus has forced migrants to take even more dangerous routes. This has led to a rise in the rate of mortality, which has increased fivefold since 2000, as well as countless injuries to border crossers.

5) Exacerbation of socioeconomic inequality. The growing illegalization and criminalization of immigrant workers reduces their power vis-à-vis employers, increasing exploitability and disposability. During the pandemic, US farm laborers, tmost of them undocumented, were declared “essential workers” and DHS announced it would adjust its policing operations accordingly. This exposes how many nation-states and the interests they serve view workers as resources to be exploited when needed and discarded when they are not. In doing so, their practices reflect and reinforce class- and race-based distinctions and their associated inequities, contributing to a world that is apartheid-like. The biggest predictor of which countries construct border walls, and where, is the wealth gap between the nation-state constructing the barrier and the place and population defined as a threat. In other words, the building of walls and policing of international mobility both reflects and produces unequal—and unjust—life-and-death circumstances.

The harms outlined above manifest the extraordinary growth in the budgets for immigration and border policing, which have increased from $1.2 billion in 1990 to $25.2 billion in 2019—a more than 2,000 percent jump in less than thirty years. Today’s budget rivals total spending by some of the world’s largest militaries: in 2019, CBP and ICE spending almost matched the military budgets of Australia, Brazil, and Italy, while exceeding those of Canada, Israel, Spain, and Turkey.

This growth reflects a political choice rather than an inevitable state of affairs. It is predicated on the purported need for massive investment in border policing in response to an ever-expanding range of manufactured threats. Yet it never seeks to address any of the root causes of unwanted migration, such as global economic inequality, intensifying climate crisis, failures of multilateral trade policy, and political violence.

As a first step toward a different path, the report highlights key demands of various migrant rights and advocacy groups, which collectively would start to dismantle the border and immigrant control regime.

The report concludes by arguing that we must move beyond a narrow debate limited to “hard” versus “smart” borders toward a discussion of how we can move toward a world where all people have the support needed to lead healthy, secure, and vibrant lives. A just border policy would ask questions such as: How do we help create conditions that allow people to stay in the places they call home, and to thrive wherever they reside? When people do have to move, how can we ensure they are able to do so safely? When we take these questions as our starting point, we realize that it is not enough to fix a “broken” system. Rather, we need to reimagine the system entirely.

By Mizue Aizeki, Geoffrey Boyce, Todd Miller, Joseph Nevins, and Miriam Ticktin

A report published by the Immigrant Defense Project’s Surveillance, Tech & Immigration Policing Project, and the Transnational Institute. Endorsed by: ACLU of Vermont, American Friends Service Committee (US-Mexico Border Program), Black Alliance for Just Immigration, Detention Watch Network, Just Futures Law, Grassroots Global Justice, Grassroots International, Migrant Justice, Mijente, Migration Technology Monitor, No More Deaths, RGV No Border Wall Coalition, and the Southern Border Communities Coalition.